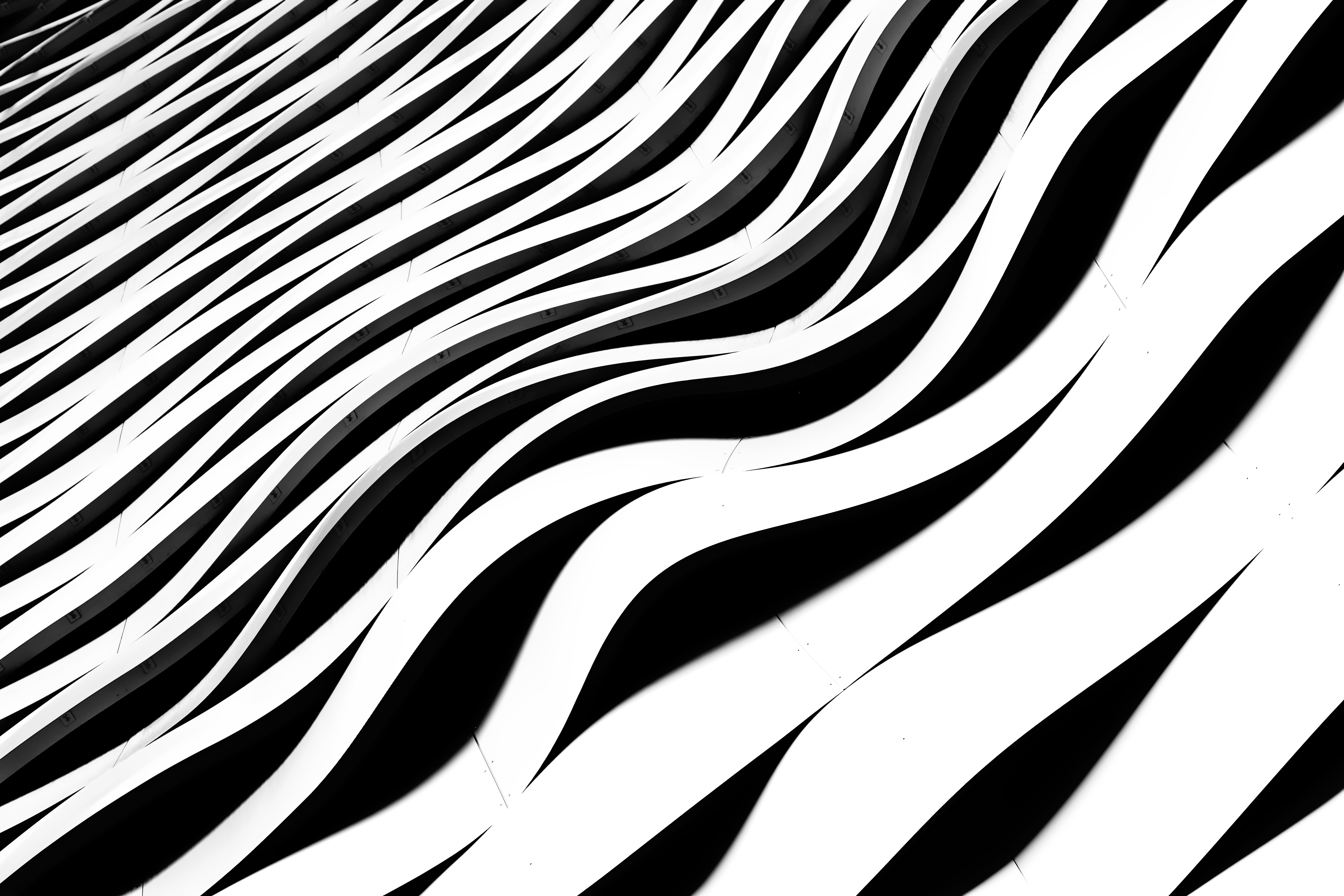

When we listen to music, our brain is trying to make sense of the patterns.

A series of posts dedicated to understanding why people like (or dislike) certain types of music and how that could help us shape the future of the classical music world.

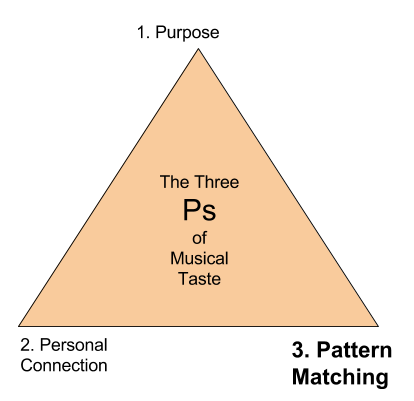

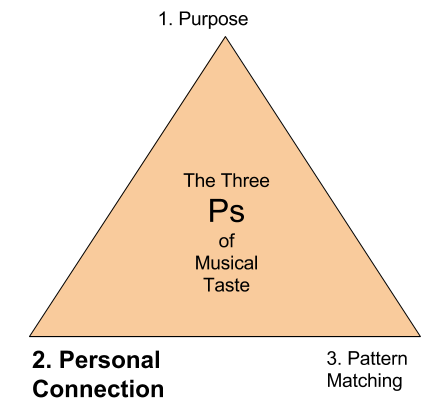

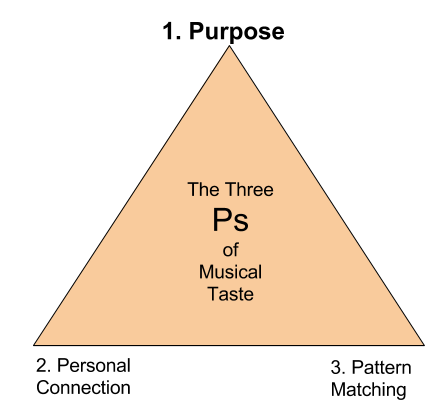

So over the last few posts, we’ve been talking about the three Ps that impact our musical taste: Purpose – why am I listening to this music? And Personal Connection – do I feel personally connected to this music somehow?

Today I want to talk about the third P: Pattern Matching. Pattern Matching means that our brain wants to know where a piece of music is heading; if it can’t make sense of the pattern of the music, we tend not to like it.

I always have an uphill battle persuading people in the classical music industry about this factor. The usual response is: ‘I don’t think people need to know (or really care much) about the structure of music.’ And it’s certainly true that only a handful of hardcore people study music theory or read scores. Meanwhile, there are thousands of classical music fans out there listening to classical music without knowing how to read a note of music. So what do I mean when I say that pattern is important?

Well, let me tell you a personal story and then share a fascinating news article and I’ll see if I can persuade you.

Only The Bits From Immortal Beloved

Gary Oldman as Beethoven in Immortal Beloved

When I was in my teens and early 20s, I had a problem with Beethoven Symphonies. I’d seen the famous Gary Oldman movie Immortal Beloved in the mid-90s, loved it and rushed out and bought the soundtrack album. (Which – quick plug here – is still probably the best single-disc Beethoven sampler album you can buy.) Because the use of the music in the film was so evocative, every track would conjure up some piece of imagery from the film for me. And I still can’t get through Georg Solti’s rendition of the Ode to Joy chorus on that CD without getting cold chills.

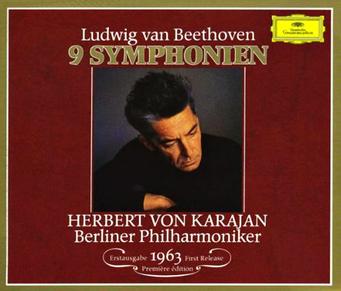

So one day I was in a CD store – I know, remember them? – and I saw the old Berlin Philharmonic / Herbert von Karajan box set of Beethoven Symphonies and decided to buy it. I was expecting to enjoy listening to all the symphonies, but that’s when I ran into my problem: I only really liked the bits off the Immortal Beloved soundtrack. The other bits were okay, but I’ll be honest – they all sounded the same. Just a sort of wall of orchestral noise. It was pleasant but it never really grabbed me.

Von Karajan’s Beethoven set: a masterpiece for everyone else, a blur of sound for me.

Then one day I stumbled across an old book on Beethoven symphonies where the author walked through each movement, explaining the structure. It was initially a bit of a struggle; things like sonata form, expositions, developments and recapitulations were all new to me. But reading the book taught me to listen more closely to the symphonies. And as I started listening closely and hearing these patterns in the Beethoven symphonies, something magical happened.

I started to like Beethoven symphonies a lot more. The only way I can explain the difference between listening to Beethoven before I knew the structure and hearing it afterwards is to compare it to watching a foreign film with no subtitles vs watching it with subtitles. Or watching a sports game where you don’t know the rules to suddenly being told what’s going on. It was like a massive light bulb went on.

Why People Hate Schoenberg’s Music

Sometime after this (but still about 12-13 years ago) I heard Daniel Barenboim speaking on the radio. Someone asked him a question about what he thought would happen in the future to classical music audiences. And he gave a reply which I’ve never forgotten. He said that audiences in Brahms’ day knew certain things about music and listened to the music differently. A hundred years later, he was concerned about the future of classical music audiences, because he wasn’t sure that audiences were listening to music in the same way.

This fascinated me because it backed up my own experience – when I knew a little bit about music theory and the structure of Beethoven’s music, I enjoyed it a lot more. Plus it opened up a great deal of other 19th century music. So was all this a music education problem? Was the issue just one of getting more people to learn music theory? And given that sonata form is buried six grades down in current music theory teaching, is it realistic to expect people to learn that much theory just to really like a Beethoven CD?

But pondering on it over the years, another thought occurred to me: what if it’s not really the rules of sonata form that is the important thing to know? What if the issue is simpler than that? What if our brains just like music to have a pattern? (Any pattern at all, really.) Thus was born the first corner of my three Ps triangle, but at the time I had no idea whether it was just me that found music easier to listen to if I could fit it into a pattern or whether it was a real thing that other people experienced.

Until I stumbled upon this fantastic article in 2010: Audiences Hate Modern Classical Music Because Their Brains Cannot Cope.

According to the article:

A new book [The Music Instinct by Philip Ball] on how the human brain interprets music has revealed that listeners rely upon finding patterns within the sounds they receive in order to make sense of it and interpret it as a musical composition.

No Pleasure From Accurate Prediction

A bit further down, the article quoted from another book by David Huron of Ohio University, who had done particular research on the music of Schoenberg and Webern particularly. He found

“We measured the predictability of tone sequences in music by Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern and found the successive pitches were less predictable than random tone sequences.

“For listeners, this means that, every time you try to predict what happens next, you fail. The result is an overwhelming feeling of confusion, and the constant failures to anticipate what will happen next means that there is no pleasure from accurate prediction.”

Now, sure, Huron was talking about Schoenberg and we’ve already discussed on this blog that many people struggle with atonal music. But assuming Ball and Huron are correct about patterns, why wouldn’t it logically hold true that an ordinary person, unfamiliar with classical music, might not be able to make sense of a Beethoven symphony?

In short, is there a divide in society between two broad classes of people? On one side, people whose brains can latch onto the sounds of classical music and follow along – and thus enjoy it. And people on the other side, who hear what I used to hear: a wall of vague orchestral sound? Could this be one of the reasons that explain why less people like classical music nowadays?

In my next article on this topic, I’ll look more at pattern matching, how this used to be a commonly recognised problem in the 19th century – and also why we tend to underestimate it as an issue nowadays.

Subscribe to receive more posts like this via email as soon as they are posted.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.