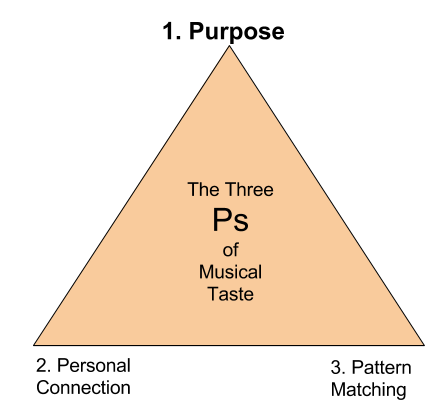

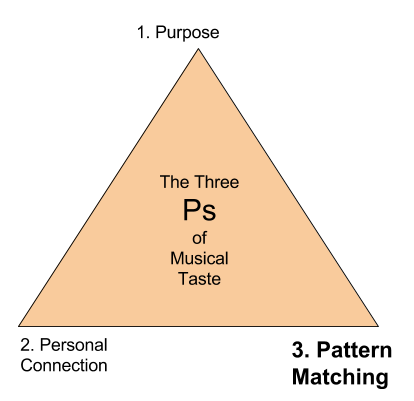

In my last post in this series, I was talking about the first P in my three Ps of Musical Taste: Purpose. We have certain purposes for listening to music and music that lends itself to those purposes is music we like.

I talked about the idea of a mismatch of purposes that might occur in a concert hall. The musicians and conductor might be performing a work of music for more intellectual reasons. It might be to showcase their performance excellence and/or the quality of the composition. Some of the audience members, however, might be there for a different purpose. They might just be there to hear some big tunes and have a good time.

Which leads to a fascinating idea that I haven’t heard explored much – but there may be research out there – and that is the concept of multi-purpose music.

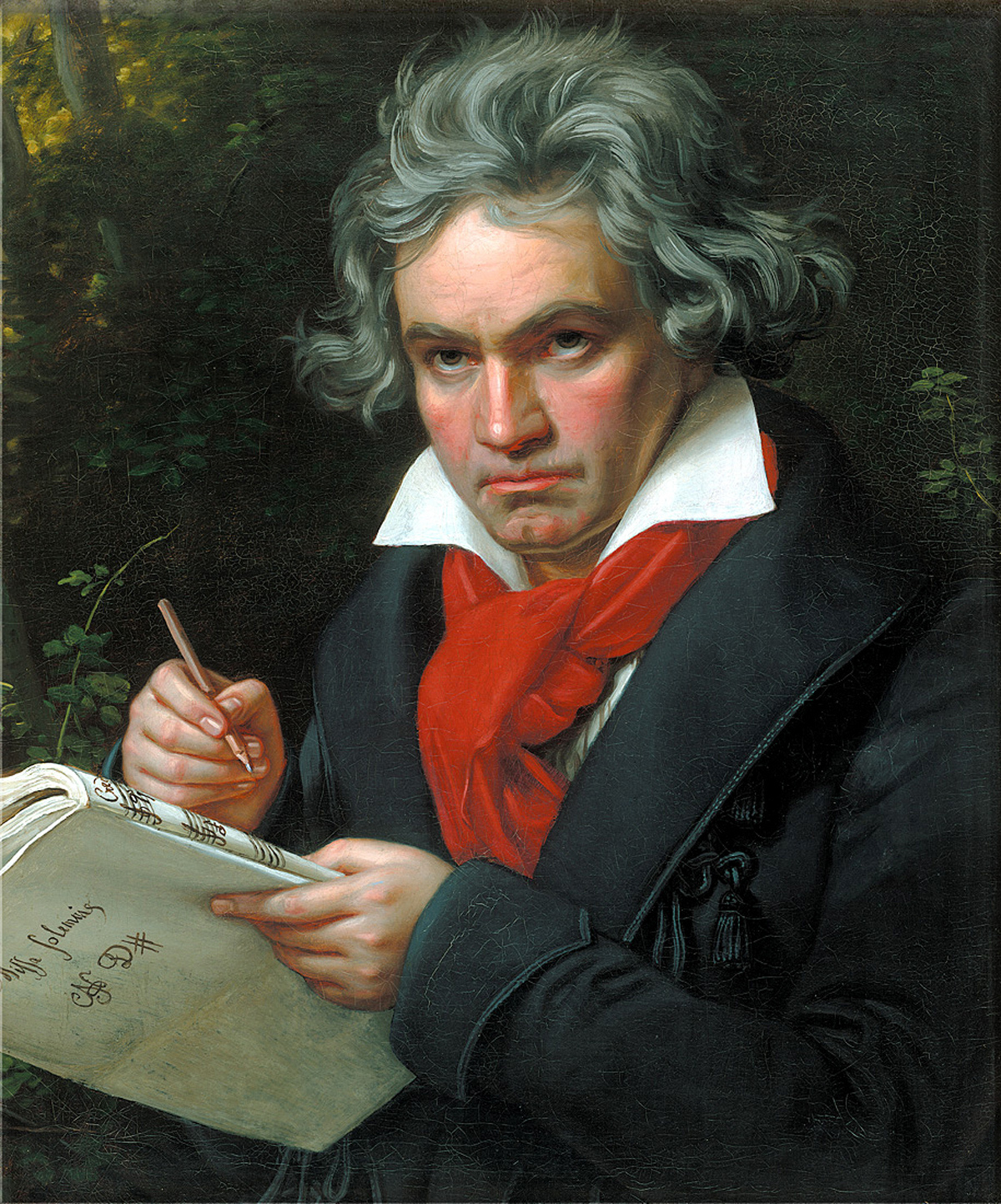

Everybody Loves Beethoven

Musicians and audiences frequently disagree over the merits of many composers. A well-educated musician might think that Webern’s music is phenomenal. A member of the audience, however, might consider it unpleasant ‘modern’ music that sounds dreadful. In fact, they might even dispute the word ‘music’.

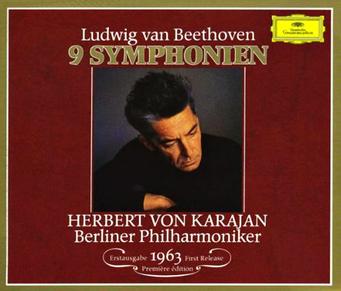

But then there are other composers that everybody loves, musicians and audiences alike. And to illustrate my point, I can’t think of anybody better than that King of the Classical Charts: Ludwig van Beethoven.

Beethoven is amazing among classical composers because nearly everyone loves his music. We may not like all of the same pieces, but Beethoven always gets plenty of entries on any sort of popular vote of Top 100 Classics. By the same token, every serious classical musician and conductor worth his or her salt also loves Beethoven. You’re not a ‘serious conductor’ until you’ve released at least one Beethoven CD – if not an entire symphony cycle.

And it’s got nothing to do with musical sophistication, either. I’ve taken people who are relatively new to classical music along to hear a Beethoven symphony and they have just as much fun as the musicians and conductors performing. (Perhaps even more so – audience members don’t have to worry about playing wrong notes or reading scathing reviews the next day.)

But take a composer like Boulez, Schoenberg or Carter and the audience doesn’t like it half as much.

What’s going on?

Multi-Purpose Music

Essentially, the music of Beethoven – and most of the composers of the 19th century – was multi-purpose. If you were a layman off the streets and your purpose for listening was altering your mood and having a good time, Beethoven would do it for you. However, you could also listen to Beethoven on a structural level or from a musicianship angle. His music has both big tunes and extraordinary depth and brilliance. Magically, his music fulfills multiple purposes at once – both emotional and intellectual.

Many composers of the 19th century seemed to work this amazing line – satisfying the masses and the musicians simultaneously.

The Crystal Palace

Likewise, concert experiences appeared to be multi-purpose as well.

On an older blog of mine, I wrote about my explorations into the Crystal Palace concerts of George Grove. These were a series of concerts in London in the latter half of the 19th century that – arguably more than anything else at that time – exploded the fan circle for classical music in that city. You can read all about it in my other post, but when I did research to look at the concert programs of the old Crystal Palace concerts, to my great surprise, they looked very different from classical concerts today.

A massive concert at The Crystal Palace.

Granted, this was in the 1850s, so they didn’t have any of the 20th century music that our audiences hate so much. Nor did they have the massive symphonic works such as Mahler and Bruckner symphonies that can quite happily chew up to 80-90 minutes of the concert running time without batting an eyelid.

But even allowing for that, the concerts were unusual. They would start with an overture to a ballet or operetta, them some light fluffy short works. (The kind of thing we’d consider ‘lollipops’ nowadays.) Somewhere in the middle they would have one major work (e.g. a Schubert symphony, a Beethoven piano concerto). This would then be followed by more light works, including some popular opera arias and songs sung by opera singers. Finally, they would have another big rousing overture to finish.

Multi-Purpose Concerts

While I have yet to come across some documentation to examine the purpose behind this arrangement of music – though it may exist, and would be a fascinating research project for anybody reading this in London with access to the Royal College of Music (hint, hint) – I can take a pretty strong guess. The Crystal Palace concerts were trying to be multi-purpose. Lots of simple, crowd-pleasers to warm the crowd up. One serious work to expose them to one of the Great Works. Then more crowd-pleasers to send them out in a good mood.

Seeing this up-ended everything I’d ever thought about classical music. Today, classical concerts are either fun or serious, but rarely both at the same time. But here were a bunch of concerts deliberately aiming at the broadest base of audience (you could even argue the lowest common denominator possible). And lo and behold – classical music took off in London and now, to this day, it is a city with a thriving classical music scene.

The 20th Century – A Shifting of Purpose

But something seemed to shift in the 20th century. Somewhere in that time period classical music concerts shifted. They went from being multi-purpose crowd-pleasers to being relatively serious forms of entertainment.

Don’t get me wrong – there are still plenty of people in the audience who come along for the fun stuff. The big tunes, the sweeping cathartic emotions. But these are those people who are sitting in the audience wondering why you’re playing all that ‘horrible’ music for them that they don’t like.

I’m sure there are many connoisseurs in the halls who appreciate the new turn music has taken. But what about the ordinary person on the street – the kind who used to get so much out of the old Crystal Palace concerts? Have they been left behind by the new concerts of the 20th century?

It doesn’t happen so much nowadays but there used to be stories that went the other way as well – of audiences who came for serious stuff being disgusted when their concerts suddenly started trying to please the masses. My favourite story about this is the one that composer John Adams tells regarding his work Grand Pianola Music, which premiered at a contemporary music festival. At the end of the work, he got ‘a substantial and … shocking number of boos’. As soon as you hear the piece, the reason is obvious. It’s fairly tonal and, about two minutes into the final movement, he introduces a hugely crowd-pleasing Big Tune. In short, he included something that the masses would like.

Now that story may not be representative of what has been going on all the time. But it does seem to indicate that the multi-purpose musical experiences have perhaps become less popular. Playing to those who want a good time as well as those who want a serious experience is not pursued in the same way.

Purpose-Driven Listening

While this is far from the only reason – and I’ll be exploring others as the series continues – I hope you can see how something like a shift in the purposes of both the music and the performances may well have been part of the drift away from classical music.

Because what purpose does even traditional classical music play for a person not into classical music? If someone listens to music for fun, does classical music sound like fun? If someone is into music for altering their moods, does classical music create the kind of moods people want? Could it meet more of these purposes under the right circumstances?

(An interesting footnotes to this is that one place where classical music is still going strong today is on music streaming services such as Spotify. But where they are going strong is in certain classical playlists. Guess what kind? They are purpose-driven classical music playlists: classical music for relaxation, classical music for study, classical music for reading, etc.)

Clarifying Purposes

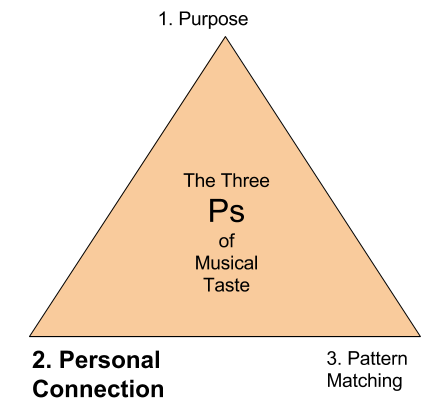

I’ll return to Purpose again in a later post. (After I’ve introduced the other two points of the Music Liking triangle: Personal Connection and Pattern Matching. But for now, here are some questions to contemplate.

For performers and performing organisations, can you explicitly name the Purpose/s behind how each performance is put together? More importantly, do you understand the purpose of the audience? If that purpose was different from the audience’s purpose for attending, what would you do?

Coming Up Next

In my next post on this Wild Theory of Classical Music, I’ll talk about Personal Connection. This is about how if we feel personally connected to a certain type of music, we like it more.

I’m currently the Director – Sales and Marketing at Queensland Symphony Orchestra. (All thoughts my own.)

I’m currently the Director – Sales and Marketing at Queensland Symphony Orchestra. (All thoughts my own.)