Classical Music 2.0 is a 10-part blog series putting forward a possible vision for the future of the classical music industry – imagining a time where we might have larger audiences, more revenue, and play a bigger role in society. (Previously: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5| Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8)

In this second-last part of the Classical Music 2.0 series, I wanted to share a couple of examples from the current classical music world which I think indicate that we are heading into a new world of how audiences are attracted to music. There are elements of some of these changes that are happening in various classical music companies (for instance, I was contacted by New Bedford Symphony Orchestra who pointed out their Musical Connections program which uses themed Spotify playlists and special events to introduce new audiences to classical music).

But where I am really starting to see traction is in the recording industry. Artists and record producers seem to be getting the idea of the new landscape quite dramatically. So in this post I want to talk about two artists who have broken fairly recently into the classical world, but without necessarily coming up the regular pathways. I think what they have done speaks to how an understanding of the new landscape of music can lead to increased cut-through and audience growth.

Víkingur Ólafsson

Víkingur Ólafsson is an Icelandic pianist, signed up with the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon (DG) label. I first discovered his music back in 2021 or 2022, when Limelight, the Australian fine arts magazine, named his recording of Debussy & Rameau, the album of the month. A few months later, it became Limelight’s best classical album of the year.

I had a listen to the album, and was almost instantly hooked. For background, I grew up learning the piano, but I’ll be honest, I have never fully enjoyed listening to hours of piano music. I don’t know what it is, but after half an hour, an album of piano music just becomes a bit too heavy going for me. But this Debussy / Rameau album was utterly compelling but I couldn’t quite work out way.

I started going down the Víkingur Ólafsson rabbit hole and became equally enamoured of his other albums (which at that time included a Philip Glass album and a J.S. Bach album). It took me a little while to realise why I liked his music so much, but I finally worked it out. It’s because his albums actually function in two ways at once: at a classical level, they are exquisitely performed, so the playing is phenomenal and the programming of fast and slow, dark and light is beautiful. So to the classical music world, he is a pianist with some interesting thematic programs and variety. Going from Philip Glass to Bach to Rameau is quite a feat.

However, at the same time, his albums are doing something else. With their spotless acoustics (they sound phenomenal on a good pair of headphones), they also double as Piano Music for Studying / Piano Chill playlists. In fact, whether it’s a canny choice on Víkingur’s part or his producers – or his musical taste just shakes out this way – but his repertoire largely consists (at least in the three albums I’ve mentioned) of short tracks, where the tempo and volume remain relatively consistent throughout a track. If he was cranking out Liszt or Beethoven albums – the path trod by many other up-and-coming pianists to “prove themselves” – his playing might be musically fantastic, but wouldn’t achieve this extra purpose of being great to chuck on in the background while you’re doing something else.

This means that when it comes to Spotify or any streaming service, Víkingur’s tracks aren’t just found in the classical section – his music features throughout all the relaxation /study / reading playlists.

This is key because it’s been well documented in a few places that the rise of classical music in the streaming world has been massive – particularly among younger audiences. However any time I have read reports on this, the results have always indicated that this is more people listening via mood and genre playlists, rather than, say, thousands of new people getting particularly knowledgeable about different classical composers. In other words, they are not like the old Brahms fans were that we were talking about in Part 6.

So in this environment, Ólafsson has spectacularly managed to play both sides of the market: he is tapping into the new up-and-coming market while also getting rave reviews from the traditional classical crowd as well.

Crossing Genres

Another feature of Ólafsson is how his various projects cross genres – further helping work the streaming algorithm in his favour. Joe Wright, the film director, has used him in a couple of film soundtracks: Winston Churchill bio-pic Darkest Hour and the semi-musical film Cyrano with Peter Dinklage. Ólafsson features in nearly every track of those soundtracks, thus cementing him in the film music playlist world – another common gateway into classical music.

Finally, he appeared on the track “God Moving Over the Face of the Waters” on Moby’s recent Reprise album, also released by DG. (The fact that DG, one of the most prestigious classical record labels of all time, worked with Moby to create a crossover album at all already seems to indicate that the label at least sees the future of the industry.) So Ólafsson is now seeded across Spotify in three different genres, a myriad different line-up of mood playlists, while not at all hurting his standing in the classical music world.

The result? Measured by the number of streams per month (around 2.7 million when I checked), it makes him the second-most popular classical pianist on Spotify (second only to Lang Lang, with about 3.5 million). By comparison, every other great classical pianist of note, living or dead, is mostly below the 1 million mark. Having so spectacularly worked the streaming system, it is little wonder that Ólafsson can now pull a packed crowd wherever he goes, and has a following that is now keen to see what type of project he tries out next.

If I ever get to meet him, I’d love to ask him whether he has consciously chosen this path, or whether it is his producers, but either way it is a spectacular achievement!

Christopher Tin

An equally spectacular achievement that is perhaps less well known is the rise of American composer Christopher Tin. I first encountered Tin when his song cycle The Lost Birds was performed with vocal group VOCES8 and Queensland Symphony Orchestra, at which time I discovered that he has been well known in video game circles for many years. In fact, his composition model is quite clever. His most popular song of all time is “Baba Yetu”, an arrangement of the Lord’s Prayer sung in Swahili for choir and orchestra. It was designed as menu music for the video game Civilization IV.

The music became so popular that Tin later added multiple movements for choir and orchestra and turned it into an-hour long choral song cycle called Calling All Dawns. Each movement in Calling All Dawns is in a different language, sung by different ethnic choirs and vocalists, and the end result is something akin to a video game soundtrack combined with world music combined with a classical cantata.

He’s since repeated this song-cycle composition style four times, often taking something that started as video game music, and turning it into a full-length composition.

Thirty years ago, Tin would probably have been dismissed simply as a “crossover” artist – because the unspoken rule used to be that only music for the concert hall or opera or ballet counts as “classical music” and composers who spent most of their time outside those genres (e.g. John Williams) were rarely counted in the same breath as the classical composers.

So in a spectacular reversal of that trend, this year Washington National Opera commissioned Christopher Tin to write the finale for Puccini’s Turandot. And apparently, according to most reviewers, it was amazing. I cannot tell you how much of a reversal this is that someone who could have been pigeonholed as a “video game composer” was allowed to complete the most famous unfinished opera of all time.

Feelgood Countdown

Finally, at the time of writing this, I can’t help but mention ABC Classic’s latest Classic 100 countdown from a couple of months ago, which featured a “Feelgood” theme, which absolutely mixed up the genre’s even more. Go check out the final list for yourself. Classical purists might be sighing at the dumbing down of music, but it is clear ABC Classic sees the future.

These are just a few examples. I could list more. (e.g. violinist Daniel Hope, who has smashed even Lang Lang out of the water with monthly listens on Spotify). But these stories are enough to indicate that in terms of recordings, radio and individual artists, a sophisticated audience-building approach is being utilised.

Which obviously leads to the question: what seems to be holding up the major classical music companies from also adopting such an approach? (And I don’t count just putting on populist concerts as “commercial” shows for money as building an audience of the future.) The answer is a complex and subtle set of barriers, and I’ll talk about them in my final post in this series next time.

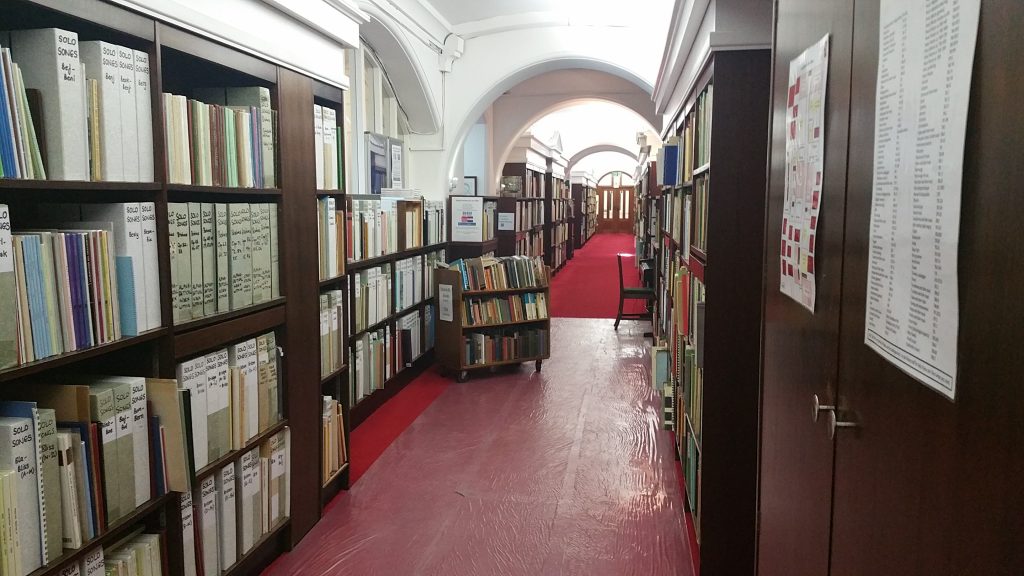

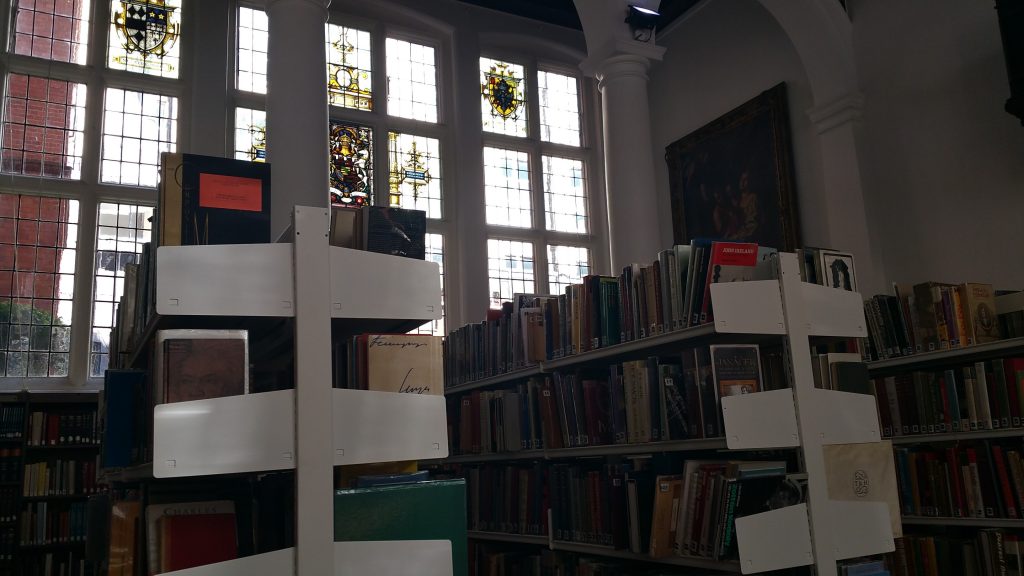

The Grove bust, just sitting there on top of a bookshelf in the reading room.

The Grove bust, just sitting there on top of a bookshelf in the reading room.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.