Classical Music 2.0 is a 10-part blog series putting forward a possible vision for the future of the classical music industry – imagining a time where we might have larger audiences, more revenue, and play a bigger role in society. (Previously: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5)

So we’ve been building the case that the audience and their familiarity (or otherwise) with classical repertoire is the primary driver of concert attendance (and thus revenue). I’ve suggested that what we have been seeing as an ageing audience crisis could also be seen as a crisis of familiarity. In short, that audiences have less of a knowledge of what used to be known as “the canon” – the great masterpieces that (at least supposedly) everybody knew.

The barometer of this (at least in Australia) is the ABC Classic Top 100 countdowns, and I mentioned in the last blog post that when ABC last polled people on their favourite piece (“the music you can’t live without“) Brahms didn’t make the top 100. This is one of those strange discrepancies between audience and musicians / conductors. Among the latter, Brahms is considered one of the greatest composers of all time. So why are audiences not on the same page? How did Brahms fall so far out of fashion?

Education as an aid to Processing Music

The mostly likely main culprit in Brahms’ decline in popularity is a lack of musical education. However, this lack is perhaps not for the reason most of the classical music industry thinks of. Often when the classical music world thinks of musical education (especially with classical music) the goal in the past has been to keep the “great works” of the past alive, or perhaps to generate an enthusiasm for classical music – music appreciation.

But one of the most important aspects of learning about classical music, particularly musical theory, is that it provides a guide for our brains in how to process the music. In Part 4 of this series, I mentioned the work of Professor David Huron and his work Sweet Anticipation, which details how we tend to experience music as pleasurable when our brains can anticipate where the music is going.

One of the things that I don’t think we’ve appreciated fully in the classical music world – even perhaps when we have been the beneficiaries of such knowledge ourselves – is that some of the basic points of music theory work to guide our listening. And not only that, but not having that knowledge makes it much harder for a listener to process the music.

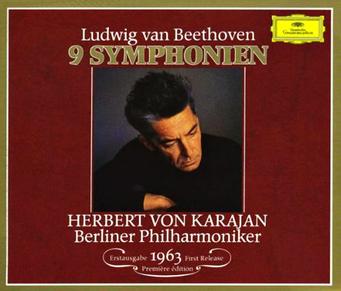

Brahms Symphony No.3 – the Pre-Requisite Knowledge

Let’s take Brahms Symphony No. 3 for instance. I want you to consider the level of knowledge that the typical die-hard classical music fans would bring to bear to listen to a piece like this. For instance, if a person with some classical training found themselves at a concert with Brahms’ Third Symphony, even if they weren’t immediately familiar with the music and hadn’t listened to it before (or not for a long while), they would know to flick open the program booklet. In that booklet, they would find a program listing that contained something like this:

Johannes BRAHMS – Symphony No.3 in F major, op. 90 (1883)

I. Allegro con brio

II. Andante

III. Poco allegretto

IV. Allegro — Un poco sostenuto

35 minutes

I’m not sure what a newcomer would make of this listing, what with its Roman numerals and Italian language (for music written by a German?). But the classically trained person, almost without thinking about it, would pick up the following:

Level 1 Knowledge

- That Brahms was a famous composer from the Romantic era. (They would pick that from the 1883 date.)

- That this is a symphony, meaning a large-scale work for orchestra.

- That Brahms wrote multiple of these symphonies and that this is his third one.

- Despite this being only his third symphony, this is his opus 90, meaning the 90th work he had published. So we can already presume he wrote a ton of music before this, making this something he wrote later in this career when he had his style fairly styled.

- The key is in F major, indicating that – at least for the opening – the mood will be in a more “happy” major key rather than a darker minor key. (Though a classically trained person will expect a lot of variance in mood for a Romantic piece.)

- This symphony, like most symphonies, is broken into sections called “movements”, rather like courses in a meal.

- There are four movements, indicated by the four subsections with Roman numerals.

- The Italian wording refers to the speed of the movement. Allegro con brio means fast and lively, for instance. Andante means a more moderate speed.

- That all four movements together will take about 35 minutes to get through.

Level 2 Knowledge

If they’re even more advanced with their musical theory, and have listened to a few symphonies, they might also know:

- That symphonies from Haydn onwards (i.e. for most of the 18th century) usually had four movements – though this isn’t a hard and fast rule.

- That the first and fourth movements of these traditional symphonies would usually be fast.

- That the two middle movements would consist of a slow movement (to contrast with the opening and closing movements) and a lighter movement usually with a one-two-three beat known as a minuet or a scherzo.

- From which the advanced listener could look at the Italian speeds above and deduce that Brahms’ symphony, even though written towards the end of the 19th century is, at least in form, following the basic pattern of many, many symphonies written before it.

Level 3 Knowledge

If they are really, really advanced in their musical knowledge (and I think most classical fans were up until the 21st century), they might also know that often the opening movement in a symphony (and some of the later ones) is written in a form called sonata form, which is a form where several themes are stated (in different keys) in an opening section called the “Exposition”, then the themes are mixed up and played around with in a section called the “Development” before the themes return in a section called the “Recapitulation”.

Now, you’re either reading this and thinking “Yeah, isn’t that obvious?” in which case, chances are you’re a part of the classical music business or a long-time audience member. If you had no idea that die-hard classical music fans bring this much knowledge to the listening experience, then congratulations, you’re probably an ordinary person who stumbled across some classical music and decided you loved it, even if you didn’t know all the stuff I’ve mentioned.

The Importance of a Listening Framework

Here’s the important thing – the points I’ve mentioned above aren’t necessarily terribly interesting, or of themselves necessarily going to make you like Brahms Symphony No.3 better than any other symphony. But they do give you a guide as to how to listen to the music. This knowledge, which as far as I know was well-known to most classical music audiences up until the mid-20th century, was the framework which guided people to be able to know how to listen to different pieces of classical music and how to anticipate what was likely to happen.

This does not make classical music a cold clinical thing, just because it utilised these sorts of frameworks. It was simply a way to create length. In the same way that the typical structure of a song (verse, chorus, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, etc) allows a songwriter to create a song that is 3-5 minutes long, the above structures of movements, sonata form, etc allowed composers to create works that run anywhere from 15 minutes to 100 minutes (!) without the audience getting lost. (Mostly. There are some long symphonies that do get a lot of people lost.)

Another analogy might be to say that the rules of a sport allow spectators to follow the action – they know roughly how long the game is, whether their team is winning or losing, whether a particular shot or goal was successful or not. Or consider film, where we have an instinctive knowledge that most films have a three-act structure with all the problems being worked out in the finale. These frameworks exist all the time in arts and sports (and many other areas of life) so that we can make sense of what we are processing.

Brahms to the Untrained Ear

So now I want you to consider a hypothetical situation: Let’s say a listener knows no classical music theory at all. They don’t even know what a “symphony” is. They encounter Brahms’ Third Symphony. How are their brains likely to process the work?

There may be better research out there that can shed more light on this, but I would say – based on Huron’s work and my own personal experience when I was younger and know a lot less musical theory – that the listener is likely to only be able to grasp onto simpler things:

- How the music makes them feel

- The melodies

- The rhythms

Most music listeners with no knowledge can pick up on these elements. But the harmonies, the symmetrical structures, the journey that Brahms created, the cleverness of the way he creates something that sounds similar to the symphonies that have gone before and yet different, the difficulty and challenge for the musicians and the conductor – many of these will not be perceived. Now you might say, “But does this matter? What’s wrong with listening to Brahms for the tunes or the feel?” And this is a fair point, except that sometimes, for some composers, creating a catchy tune wasn’t the top priority for the piece. In many cases, symphonies can be far more about how themes are changed or developed over time and combined in different ways, than whether the themes themselves have a good hook.

Tune and Mood

In my years in the business, I have spoken to many, many audience members that I ended up sitting next to at concerts or met in the foyers or attended some of my pre-concert talks. And it has become apparent that the depth of knowledge that used to guide extensive and deep listening of classical music has started to dry up. As the music education part of the pyramid has dried up, people have started listening to classical music in simpler ways.

This, I believe, is the driving force behind the shape of the ABC Classic 100 and the connection between familiarity and sales in orchestras around the world. Left to their simpler listening devices of tune and mood, the pieces that are staying firm on the favourites lists are those pieces with either clear “hook” tunes that everyone knows (e.g. Beethoven’s Choral Symphony, Bolero, Saint-Saëns Organ Symphony) or pieces with a clearly defined mood / theme that is easy to grasp (e.g. The Four Seasons, The Planets). Pieces that require more knowledge of structure and form, with less easily memorable themes – like most things by our friend Brahms – are disappearing from the mental canon of our potential audiences.

And that mental canon is crucial for the financial future of our organisation. For the average ticket-buyer, if they see an ad for “Beethoven Symphony No. 5”, your success at selling the ticket will almost certainly depend on whether that person has a good idea in their head of what Beethoven’s Symphony No.5 sounds like already. (I would add that even for the so-called “commercial” concerts, this is important. It’s not just enough for an orchestra to create a concert of movie music or video game music. It must be movie music or video game music that, on the whole, is already familiar to the audiences.)

This type of idea does get raised in the halls of classical music organisations from time to time, but it’s not one that the industry likes to dwell on too much, because it seems to only lead to one conclusion: playing the same old Top 20 pieces that everyone likes to hear.

But I want to put forward a new framework: what if, by embracing this limitation of audience familiarity, we could chart the pathway back to larger, smarter, more diverse audiences? What if, simply by acknowledging that audiences today are not the same now as they were 50 years ago, we could see a way forward? This, to me, is what Classical Music 2.0 could look like.

More on this, in the next post.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.