Note: I originally wrote this blog post series about George Grove (my classical music hero) back in 2016 on an old blog. Back then I had been in the industry a few years and was thinking about a lot of big questions like: How do we make people like classical music? How do we grow audiences? But it was theoretical back then, and not yet practical. But now after 5+ years of running an orchestra Marketing team, I have tested ideas and seen how they work. The years have reinforced the lessons I have learned from George Grove, not diminished them.

Also, there is a power to story. I have found when I’ve been trying to explain ideas (particularly to musicians and artistic types) that marketing speak and audience data can make people’s eyes glaze over – but this story seems to connect. Hope you enjoy it.

I’ve lightly updated these posts from their original form. This is Part One of Five and I’ll post the rest of the story in coming weeks.

In March 2016, when I first wrote this, I was just over a month away from making my first-ever (and still first-only) trip to London. While I was going for a wedding, I decided to seize this rare opportunity to go hunting for any information that I could find about a particular person – namely, a guy named George Grove.

I’ll get back to why I was interested in George. But let me start with a question: Have you ever had a life-changing moment? Something that, perhaps, you could look back and say, “Yep, that’s one of the major turning points in my life right there.” In some cases, you might have known right at that moment that this was a big thing (like births, deaths and marriages). But sometimes life changes in major ways and you didn’t realise it was happening until much, much later.

It was this kind of change that happened to me just after the turn of the century, and it all started in the building in the photo above – Archives Bookstore in Brisbane. And precisely because I didn’t realise that this particular visit to a bookstore was going to be so momentous, I actually can’t remember the year or even the time of year. I suspect it was 2000 or 2001, but I couldn’t be entirely sure.

Archives, if you ever find yourself in Brisbane, is a big old rambling bookshop where you can find everything from old rare editions through to shelves of pre-loved sci-fi and fantasy, and piles of odd stuff everywhere.

Somewhere up the back, if you wander far enough, is the music book section. Possibly, the reason I was interested in music books was because back then I’d been reading through Phil Goulding’s Ticket to the Opera, which is a fantastic friendly guide to learning about different operas and I wanted to read more like that. Whatever the reason, that day in Archives I stumbled across a little blue paperback that looked brand new amidst the piles of otherwise well-loved books. (Maybe it was donated by some music student who was supposed to read it but had never bothered to crack the cover? I’ll never know.)

This was the book:

The book offered to take you through the music of Beethoven’s symphonies, almost note by note and – perhaps the most friendly aspect of it – in the preface, Grove said it was written for amateurs.

Of course, when Grove was writing his book (and this was in the late 1800s), the definition of an “amateur” was a bit different. An amateur was somebody who could read music (the book is filled with many musical score examples) and understood music theory – so stuff like sonata form, major and minor keys, movements in a symphony (all of which I feel would need to be explained to amateurs today), were all assumed to be understood by his readers.

So when I first started reading it, I had to work hard consulting music dictionaries and such-like stuff to try to understand what the heck he was talking about. (And I can only thank my father and his piano lessons for teaching me how to read music, otherwise I don’t think the book would have meant anything at all.)

But I persevered, and as I read, something jaw-dropping happened.

The book solved a problem I didn’t realise I had with Beethoven symphonies.

To explain: A few years earlier, I had seen and loved the famous Gary Oldman Beethoven film, Immortal Beloved. And I’d enthusiastically bought the soundtrack awhich I still think, to this day, is the greatest single Beethoven album anyone can own.

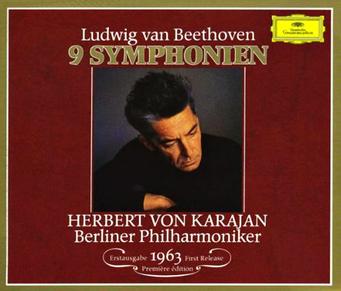

Then, thinking that I should expand my horizons and get into all of the Beethoven symphonies, a bit later I bought – because it was always the cheapest set of Beethoven symphonies back in the late 90s – the recordings of Herbert von Karajan conducting Berlin Phil. In fact, this exact box set here:

But I seemed to run into difficulties listening to it. All the Beethoven symphonies have four very distinct movements (except for the “Pastoral” Symphony, No. 6, which has five movements). But instead of hearing 37 distinct movements, the CDs always seemed to sound like this:

Symphony 1 – Nice Orchestral Background Music (NOBM)

Symphony 2 – More NOBM

Symphony 3 – First five minutes I heard off Immortal Beloved followed by another 40 minutes of NOBM

Symphony 4 – NOBM

Symphony 5 – Opening famous bit; another 25 minutes of NOBM

Symphony 6 – Some NOBM with that bit with the storm and the country dance – this one was a little easier because the tunes were vaguely familiar from Fantasia

Symphony 7 – NOBM – that great second movement (the Allegretto) where Beethoven’s nephew tries to shoot himself – More NOBM, albeit a bit more up-tempo

Symphony 8 – NOBM leaning towards random

Symphony 9 – What, a whole hour of NOBM before I get to the famous part with the choir? Why can’t he just skip to the good bits? (That said, there are possibly still hugely educated music fans that ask the same thing about the Choral Symphony.)

But, after reading Grove, I discovered that the Beethoven symphonies came into sharp focus, and all of a sudden I felt like I understood a) what Beethoven was trying to do and b) why the music was the way it was. So now listening to the Beethoven Symphonies became like this:

Symphony 1 – Movement I: Energetic opening with the first chord that shocked listeners; Movement II: beautiful little movement with the heartbeat on the timpani; Movement III: Beethoven’s first symphonic scherzo, so fast and furious it could never be mistaken for a traditional minuet (even if that’s what Beethoven called it); Movement IV: The joke with the slow scale at the beginning, like a nervous rodent poking its head out of a hole, clearly Beethoven’s sense of humour.

Symphony 2 – Movement I: unmistakable because of its fiery violin parts; Movement II: The slow movement with the intense climax at the end; Movement III: the scherzo where snippets of the tune get thrown between different groups of the orchestra like a football; Movement IV: The awesome one that sounds like a particularly crazy episode of Bugs Bunny or The Roadrunner.

Symphony 3 – Movement I: 15 minutes of epic grandness, with a huge sweep from the opening theme to the barricade-storming final minutes of the finale; Movement II: One of the greatest funeral marches ever written; Movement III: The scherzo with all the flash and fire of a cavalry charge; Movement IV: One of the most clever things Beethoven ever wrote, a theme and variations, with a theme at the beginning that sounds so light and fluffy, you wonder why he put it at the end of such a heroic symphony – until it spectacularly transforms into a thing of majesty and light at the end.

You get the idea.

But I found something had changed as well. Now having a knowledge of what the music was doing, combined with the enthusiasm of George Grove’s prose, all of a sudden, my enjoyment of the music – which up until then I had already thought was pretty high on the scale – increased tenfold. I now understood that previously when I had thought I was listening to classical music, I actually wasn’t. I was only hearing it. But now, for the first time, I understood what that sound world was that was inhabited by musicians and conductors and long-time fans of classical music. I understood why they went back to it time and time again.

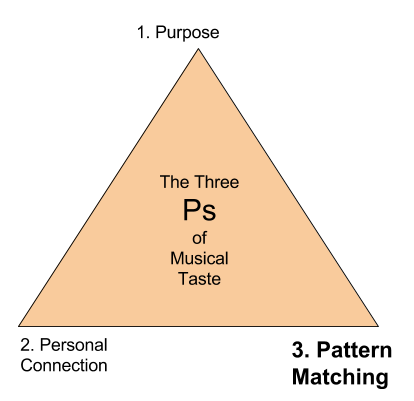

As I pondered a bit longer, a theory began to crystallise in my mind: Perhaps people aren’t ignoring classical music because they’ve had a listen and it’s not for them. Instead, what if they don’t actually really know what it is they’re hearing. The music is like a foreign film with no subtitles or a spectator sport where you don’t know the rules and can’t follow the game. Classical music is just meaningless sounds.

So – what if you could turn the subtitles on? What if you could teach the rules of the game to the ordinary person on the street, in language they would understand? Would more people then have the epiphany that I got from reading Grove?

It took several years for this idea to emerge, but that idea so took hold of me that I left behind my career path in mathematics and statistics, which I had studied at university, and spent two years trying any which way I could to get into the classical music industry. When I eventually got in (and I’ve been in this business since is 2007), I still regard it was one of the best life decisions I ever made.

So looking back, you could definitely say it was that trip to the bookstore, and picking up that book, that changed my life.

But it wasn’t until I’d been in the business for several years that I got curious about the man who wrote the book. Who was George Grove? Clearly, he had a drive to share classical music with people as well, but where did that come from? How did he act that out?

I’ll talk about that in my next post about A Guy Named George.

I’m currently the Director – Sales and Marketing at Queensland Symphony Orchestra. (All thoughts my own.)

I’m currently the Director – Sales and Marketing at Queensland Symphony Orchestra. (All thoughts my own.)