Note: I originally wrote this blog post series about George Grove (my classical music hero) back in 2016 on an old blog. I’ve lightly updated these posts from their original form. This is Part Four of Five and I’ll post the rest of the story in coming weeks. If you’re just joining me, here are the other parts:

A Guy Named George – Part 1: The Book That Changed My Life

A Guy Named George – Part 2: The Man Who Changed My Life

A Guy Named George – Part 3: The Engineer Who Brought Classical Music to the Masses?

If you’ve been following along with the previous posts then you’ll know I’d ended up in London in April 2016 trying to work out the secret of George Grove’s success in the classical music field. In the last post, I described how looking at George’s biography and a bit of sleuthing around Wikipedia led to the astonishing conclusion that in the latter half of the 19th century, Grove – a non-musician, from a working class background, running a series of concerts with an (arguably) second-rate orchestra with the same conductor every week, performing for an audience so unsophisticated it didn’t even know to sit down while the music was playing – was able to out-perform his more sophisticated rivals, the Philharmonic Societies (the Royal and the New).

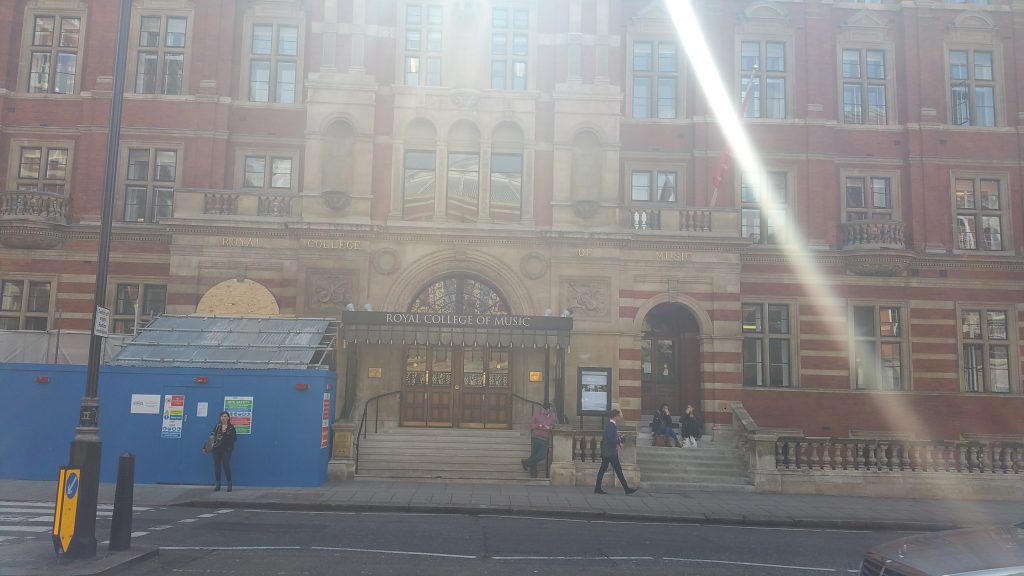

I was madly curious to know what actually happened at these concerts of his in the Crystal Palace to make them so successful. For that, the internet wasn’t helping so much. So there was only one place to go – the closest thing that you could call a “home” for George Grove in London – The Royal College of Music, still regarded as one of England’s best music schools.

I had lined up a chat a few weeks before with Dr Peter Horton, who worked in the RCM library. He was amazingly helpful, and a fount of knowledge on all things to do with concerts in the 19th century. I know musicologists and researchers are probably used to these sorts of things, but as a lay person completely new to any sort of historical sleuthing, being able to chat to people who are full of knowledge and stories about a past era is nothing short of astounding to me.

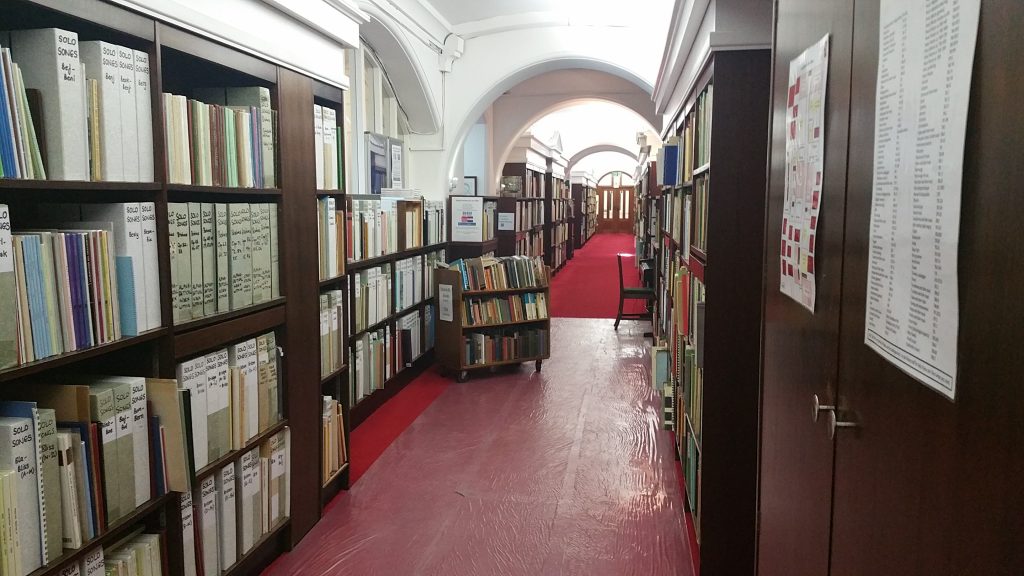

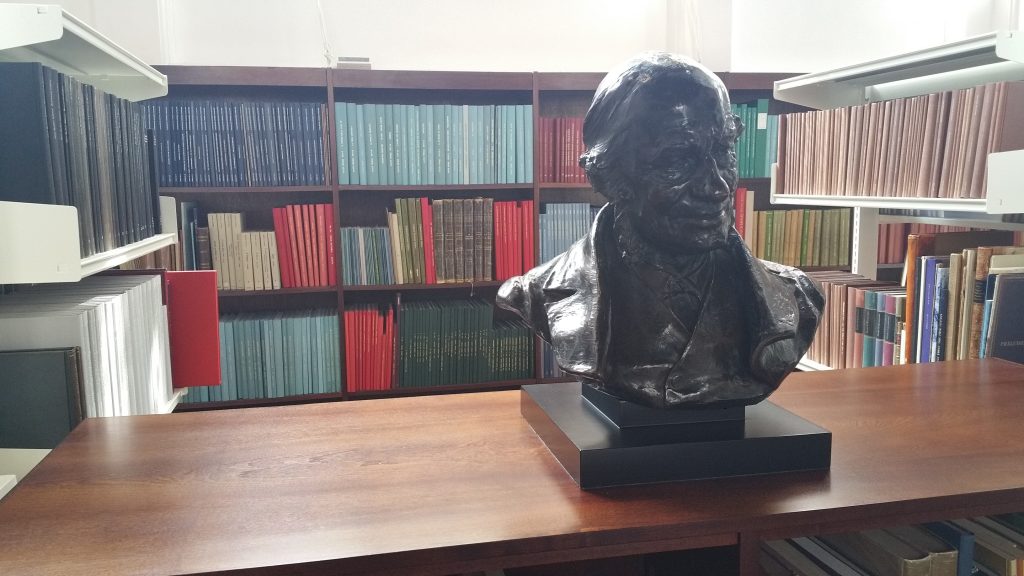

After our discussion, I got to visit the Reading Room of the library. This itself, was a powerful experience. Because as well as being a charming old-school academic reading room right there, sitting on top of a bookshelf overlooking the reading tables – was Grove himself.

The Grove bust, just sitting there on top of a bookshelf in the reading room.

The Grove bust, just sitting there on top of a bookshelf in the reading room.It’s a slightly larger-than-live carved wooden bust (there’s a matching one in the room next door for Elgar) with no name caption – but there is no mistaking those mutton-chops. It was George and it was like he was waiting for me.

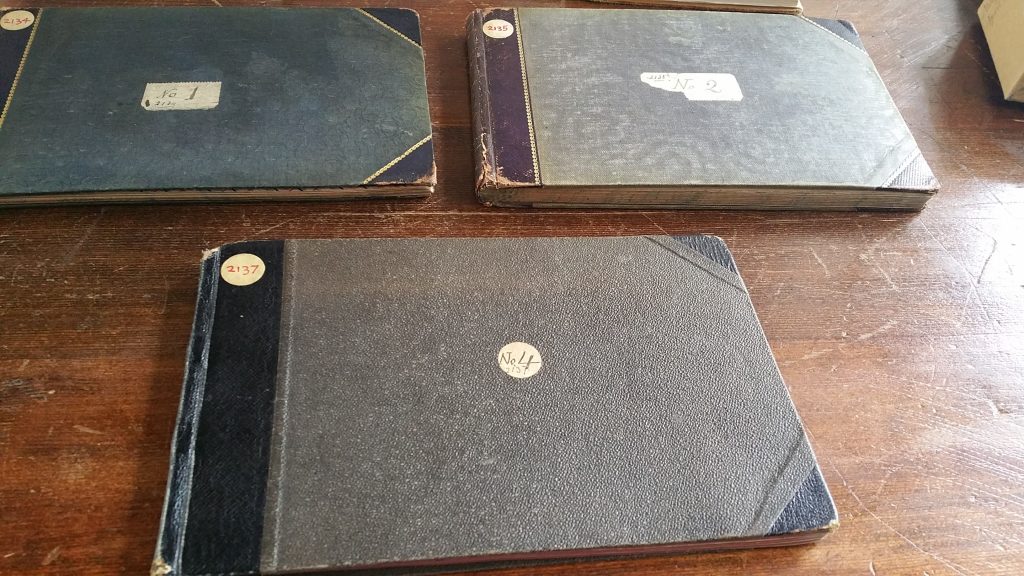

I only had a few hours, so I decided to check out a couple of books on Grove and the Crystal Palace days, some of the old Crystal Palace programmes and a couple of examples of Grove’s “commonplace books”.

The commonplace books took my breath away, because I’ve never been connected with someone from the past so intimately before. To look at, a commonplace book is just a small hardbound book with blank musical staves in them. But this was more than blank sheet music – this was the equivalent of George Grove’s iPod favourites playlist. (Substitute whatever personal device you listen to your music on nowadays.)

In the 19th century, when recorded music was still several decades away, what did you do if you really loved a piece of music, especially a symphony or something that required a large number of musicians? You might be lucky to hear it half a dozen times in your lifetime. And so, almost as a way of carrying the experience around, Grove had his commonplace books.

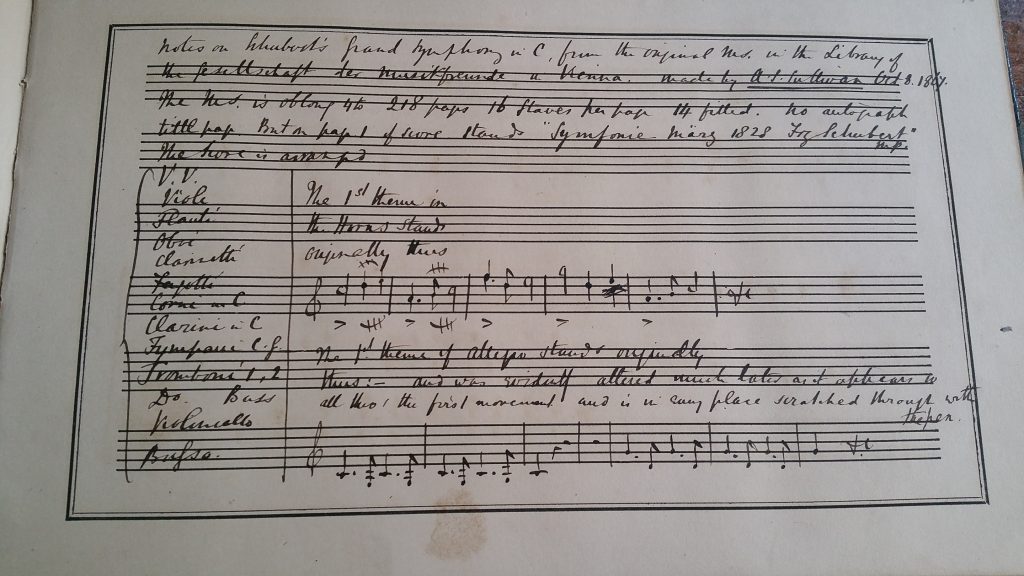

Any time Grove came across a musical idea that he particularly liked, he would make his own copy of the sheet music. Never the whole thing – you would have had to buy the sheet music for that – but maybe a theme that caught his ear. His favourites were clearly Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Schubert because they cropped up again and again. So here, for instance, is the majestic French horn opening of Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 (“The Great”). Which sounds like this for those who can’t read music.

I can just imagine Grove, flicking through his commonplace book, seeing that notation of the opening of the Schubert symphony and hearing the French horns firing up in his imagination. It made me wonder how many times he got to hear that symphony live in his lifetime. Did he listen extra closely every time he heard that theme, knowing that it would be several years before he’d get to ever hear it again. And, later in life, did he listen to it wondering if this would be the last time he would ever hear it?

The whole thing was utterly moving.

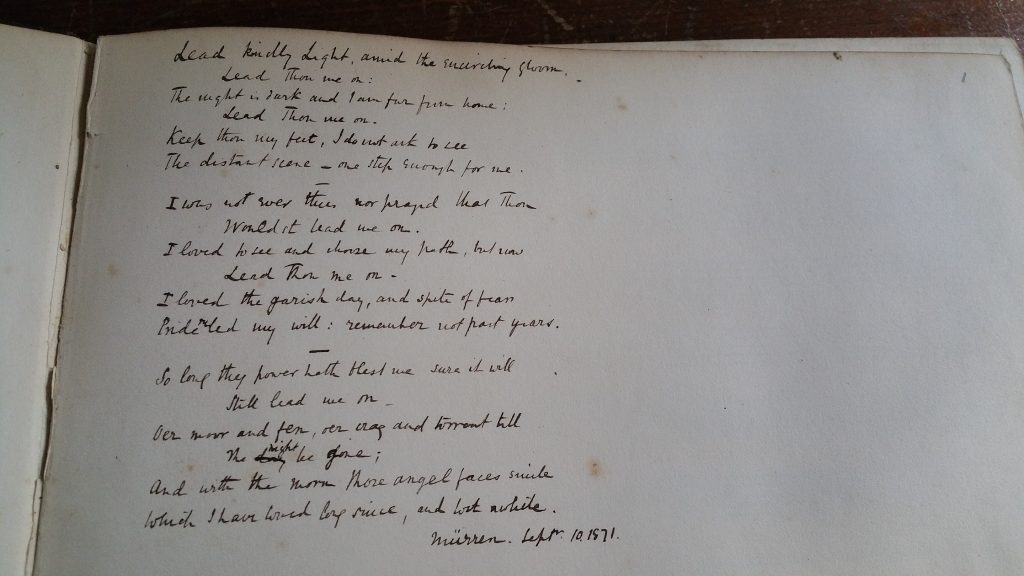

And there were little quirky things – on one of the blank pages inside the commonplace book, he had written out in full the words to a hymn “Lead Kindly Light”. Why did he do that? Did he like that particular hymn tune? As a man who dug into his faith intellectually (he was a huge enthusiast for Biblical archaeology when he wasn’t doing music) but struggled with doubts, were these words a comfort for him? We’ll never know 100%, but it was fascinating.

And then on to the programme notes:

Very quickly I found out something amazing about these programme booklets. They weren’t just a random copy of the printed programs that had been kept for posterity. These were Grove’s own copies of the booklets. Flick through half a dozen of them and you’d find his familiar handwriting (and the ink of his fountain-pen or whatever pencil he had to hand, still just as dark and clear today as it was 150 years ago) scattered throughout. Holding it, you could just see him sitting in the Crystal Palace listening to the orchestra playing. He would think of a random idea, or perhaps something that he could have said differently in his notes, whip out his pen, and jot down his thoughts. That night, he’d add the program to his growing collection of the little booklets that were the trademark of that concert series.

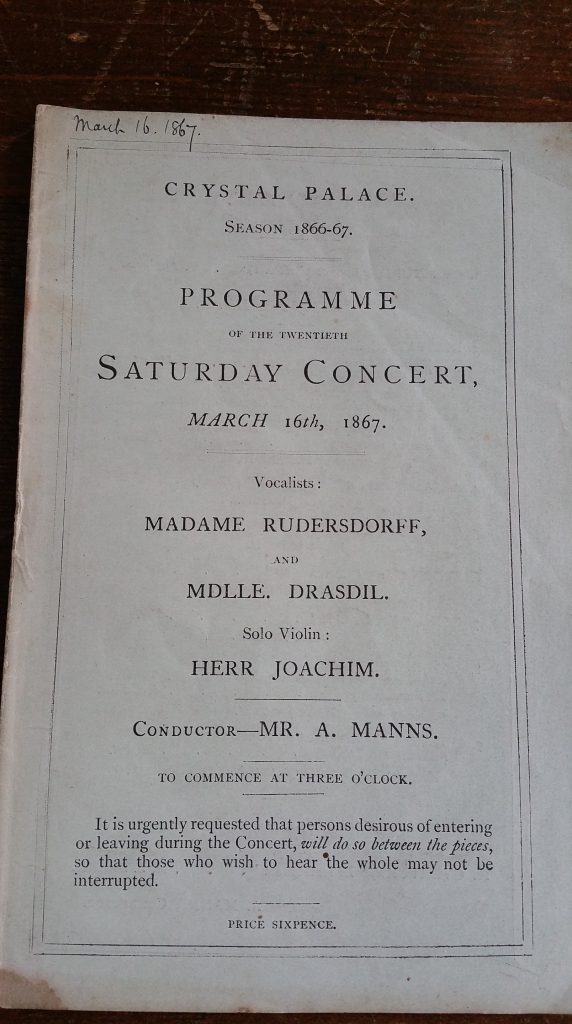

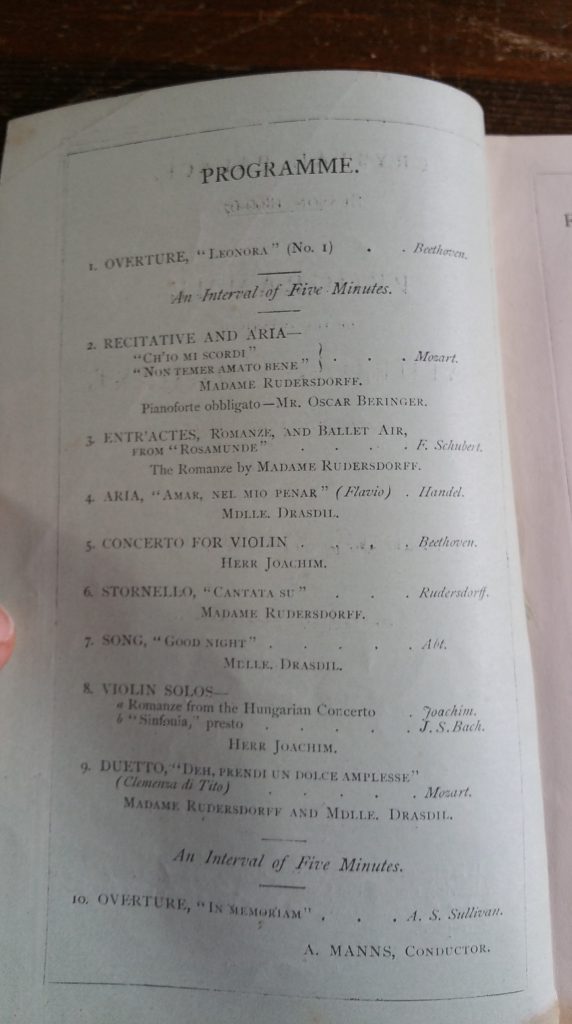

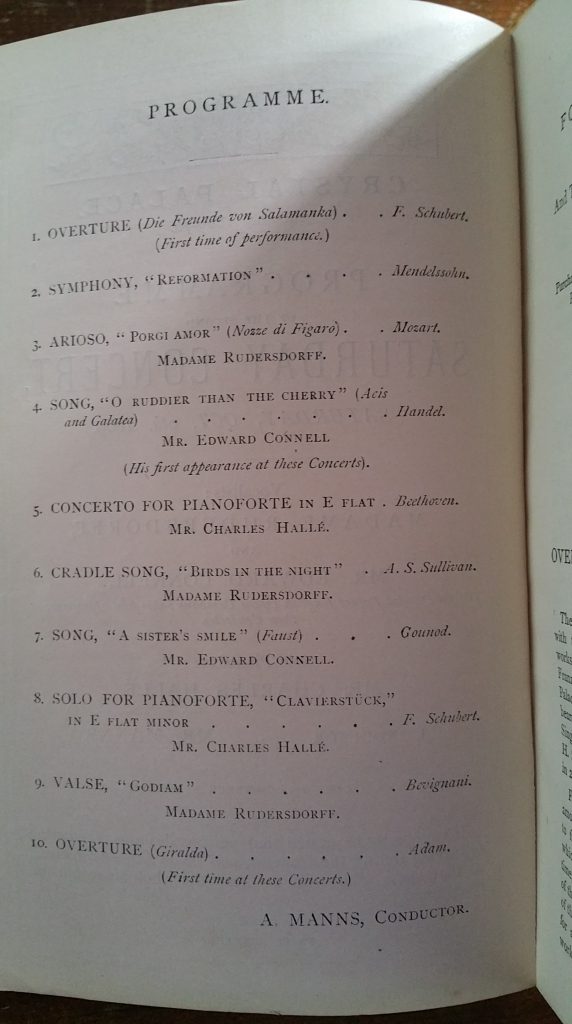

But the really jaw-dropping fact emerged soon after I started checking out the second page of the programmes – the list of works that were to be performed at each concert. Suddenly, the penny dropped for me; I realised how he had gotten the crowds and grown his audiences. Look at this program – it’s a typical Crystal Palace Saturday afternoon concert program:

There were many, many concerts that had this sort of format – they would start with an overture (the opening music, if you like) from a ballet or operetta that was popular at the time. Then there would be a curious 5-minute interval. (Only 10 minutes into the concert!). Then after that a long classical work, like a piano concerto or symphony by Beethoven. Then a couple of singers would appear to do a number of popular arias from operas and others songs that are now long since out of popular rotation. There would be another 5 minute break and then one more final overture, followed by a bit of organ music for the next half hour while you got a chance to walk around (or “promenade” as they called it back then).

For those who aren’t used to classical concerts, let me say right now: this is completely different from how we do concerts today. This is the equivalent of starting a concert with 10 minutes of John Williams’ music from Star Wars VII, playing a major classical work, bringing out some singers to do a bit of popular musical theatre, and then finishing with some all-guns-blazing piece of crowd-pleasing orchestral action – like Thomas Bergersen, for instance. (If you’re sceptical, just listen to the last couple of minutes of that Sullivan “In Memoriam” overture that ends the concert. Totally designed to have the crowd roaring on their feet.)

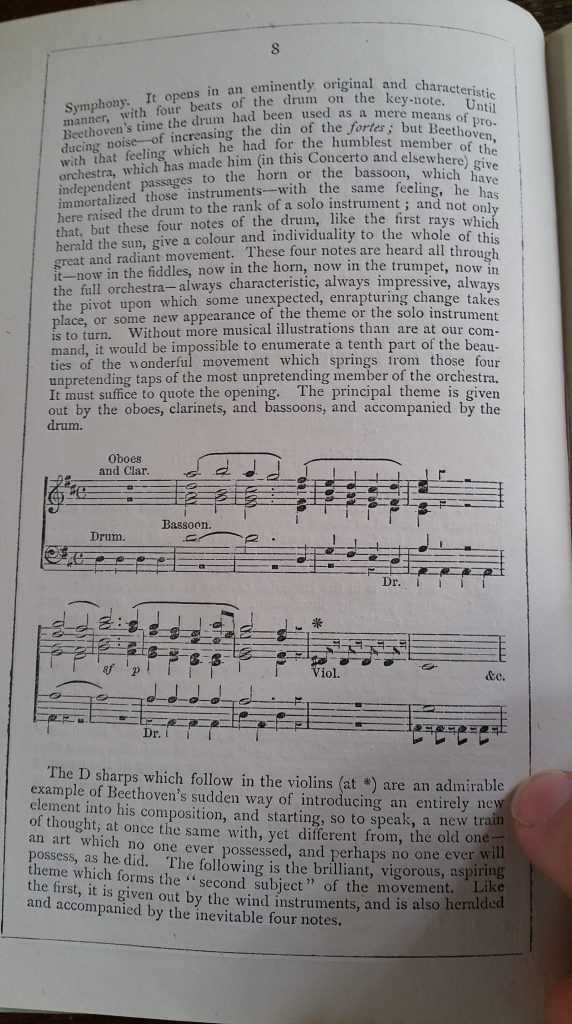

But lest you think the Crystal Palace just sounds like a glorified 19th century André Rieu concert, flicking through the programme notes, we see that in the middle part, where they did the serious music, they were pretty determined to turn the audience into classical music nerds. They’d play the whole work, and Grove’s notes were thorough and methodical. He didn’t hold back from explaining key changes, sonata form structure and the other musicological stuff. His language was enthusiastic and he was aiming at the lay-person, but he was determined that the lay-person could learn to love this music at the same level as music aficionados.

In short, Grove was putting on a show that attempted to both please the crowds and yet make them more sophisticated at the same time. In short, the whole thing was built around the audience and it was designed to be fun. The dirty little secret of the Crystal Palace and their audience growth was finally out. The reason it took off was because they were giving the audience a good time. No wonder the poor old Royal Philharmonic Society couldn’t compete!

And clearly it worked. I looked through programs from the 1850s and then some from the 1860s and in a decade, the noticeable change was that the concerts had moved from having one lengthy major work to having two a decade later. (So an 1860s Crystal Palace would still start with light fluff, end with light fluff and have light fluff in the middle, but it might contain a concerto and a symphony mixed in the middle somewhere.)

I can’t prove this without doing a lot more research, but the evidence points to Grove’s “audience-first” approach starting to pay off. It took time, but gradually, his audience was getting a longer attention span and growing in sophistication.

Next time in this series on George Grove, in my final post on him, I’ll cover off why I think his influence died out, and what we can learn from him in the 21st century.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.

I’m a former marketer / arts administrator in the Australian classical music scene, and was privileged to work for three of the major classical music companies.

Leave a Reply