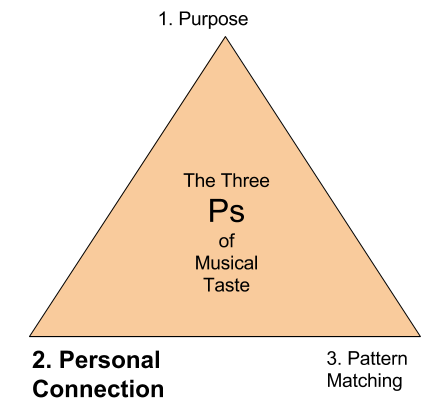

A series of posts dedicated to understanding why people like (or dislike) certain types of music and how that could help us shape the future of the classical music world. In this post, I’m looking at the 2nd P in my 3P model of Musical Taste: Personal Connection.

Photo by John Price, sourced from Pexels.com

What do I mean by Personal Connection? I would describe the idea of Personal Connection like this: We are more prone to liking music if we have a personal connection to the music itself.

The Enigmatic Robert Jourdain

So where did this idea come from? Well, a few years ago, I read a fascinating book called Music, The Brain and Ecstasy by Robert Jourdain, published in 1997. Jourdain is somewhat of a mystery to me. He’s listed on the back of the book as being a musician and a composer, but – apart from this one book – I can’t find a trace of him on the internet anywhere. Maybe he’s a guy who tinkered with music in his spare time and decided to write a book about the brain and music? I’m not sure. But it’s well worth reading.

Despite its title, the book is not about the rave scene. Instead, it deals with the mysterious issue of what our brain does when it hears music and how it processes it. Towards the end of the book, Jourdain gets to the question of why people like certain types of music and not others. (And given that he mentions classical music an awful lot in the book, I’m guessing that he possibly shares my curiosity about why people do or do not like this type of music!)

Peer Pressure

In one of the later chapters, Jourdain lays out all sorts of fascinating ideas about why we like certain music. He describes how different people have different listening styles. (Note to self: I should come back to that in another post.) But in the end, he ends with this gob-smacking quote:

[D]espite all these factors, research shows that most people largely make their personal musical choices for reasons that are neither “personal” nor “musical”. Rather, they listen to conform, taking on music as an emblem of social solidarity with their peers, each generation adopting its own conspicuously different styles. There are many exceptions of course, but the gross statistics are damning. Most people acquire their musical taste during adolescence among friends of the same age, and they carry early preferences right through to the grave. This powerful force overrides considerations of individual neurology and personality. It is a shocking observation, or at least ought to be, given the complexities of music perception. By all rights, any group of twenty teenagers ought to prefer twenty kinds of music. (p. 263)

Now, there is no footnote in the book to explain the ‘damning’ gross statistics on this. So I can’t really say where he got this idea from.

But doesn’t it intuitively make sense? (Especially if you’re Gen X!)

Turn That S*** Off!

Your mind flashes back to some awkward teenage party. Some brave soul goes over to the communal sound system. (This could be a parent’s hi-fi or possibly just a cheap boom box.) They put on a CD (or a record, if you go back far enough), hoping the room will like it. Within seconds (not minutes), someone pipes up with: ‘Turn that s*** off!’ We’ve all been there, right?

Now some of us may have had a robust nature as a teenager. We persisted in maintaining our musical taste despite what everyone else thought. But how many of us tended to drift towards What Everyone Else Was Listening To? Or, more particularly, What People Like Me Are Supposed To Listen To? Isn’t that what commercial music radio is all about? Playing the music that Everyone Like You likes so you can keep up with the times?

Once you start thinking about the whole idea of Personal Connection, you can see it in a lot of places. (I was originally going to call it ‘peer pressure’ in honour of the Jourdain quote, but Personal Connection has more positive connotations, I think. Besides, it’s not always a negative thing.)

Some Familiar Situations

Consider some of these situations which you might have found yourself in:

- You’re at a friend’s place and they start talking about a band or musical artist that they love, but it’s a genre you don’t normally listen to. You ask them to send you a link to it on Spotify. Even if you don’t like the music, you have decided to give it a listen, because you’re trying to see what your friend is so excited about.

- You keep hearing people at work talking about some singer or band that they love. Four of them have tickets to their next concert. You decide to jump on YouTube and have a sneaky listen.

- In case none of that was ‘classical music’ enough for you, how about this one? You’re at a concert. There’s a work on the concert program that you’ve never heard and You’re Not Sure That You Will Like It. But then the conductor gets up and gives the audience a two-minute spiel at the beginning, talking about why the music is so awesome to him or her and a couple of things to look out for. All of a sudden, you’re listening closely to the music, trying to catch the bits that you’ve been told are super-exciting.

These are just a few examples, but you get the idea. You have listened to music you wouldn’t normally have listened to (or listened more closely) because somebody expressed their enthusiasm for it. I’m not saying you loved it. I’m not saying it was an instant favourite. But you were subtly pushed up the Music Liking scale from ‘Not Interested At All’ to ‘I’ll Give It A Try’.

This is Personal Connection at work.

Classical Music Affinity: Measuring Personal Connection

Another fascinating stat that backs up the idea of Personal Connection is the idea of affinity. One of my favourite arts blogs is Know Your Own Bone by Colleen Dilenschneider. Colleen mainly writes for the museum sector, but a lot of what she says is applicable to the classical music world as well.

She recently put together an excellent set of statistics on the idea of attitude affinity. Attitude affinity is a simple one-question measure of how somebody feels about something. The question is:

On a scale of 1-10 (1 = Less Welcoming, 10 = More Welcoming), is [Cultural Organisation / Artform ] welcoming to people like me?

One of the survey questions in Colleen’s data was the statement: ‘Orchestras and symphonies are welcoming to people like me’. The result? For nearly half the adults surveyed, their perception of them being welcome was low enough to ‘pose a significant barrier to their onsite engagement’.

In short, when a large number of people think about orchestras – they don’t think they are for people like them. Now that may not be true. (I’m sure most orchestras would say they want to welcome everyone). But that perception alone is enough to stop a whole bunch of people coming in to hear the music.

Why?

So the question becomes: well, why are people thinking this music is not for them? Those of us on the classical music side of the fence sometimes get a bit surprised by this. After all, we really are happy to have anyone come along to a concert. Nearly every classical music organisation has some sort of cheap ticket deal for young people and new audiences to get them in.

In other words, we never told people that classical music wasn’t for them. We’d like to think that this music is for everybody. So where did people get the idea it wasn’t for them? And what can we do to change that perception?

This topic is getting bigger as I write about it, so I’ll end this post here, but in my next post in the Wild Theory series, I’ll talk about Unconscious Personal Connection Trigger Points: the things which, perhaps subconsciously, lead us to feel more or less connection to music.

I’m currently the Director – Sales and Marketing at Queensland Symphony Orchestra. (All thoughts my own.)

I’m currently the Director – Sales and Marketing at Queensland Symphony Orchestra. (All thoughts my own.)